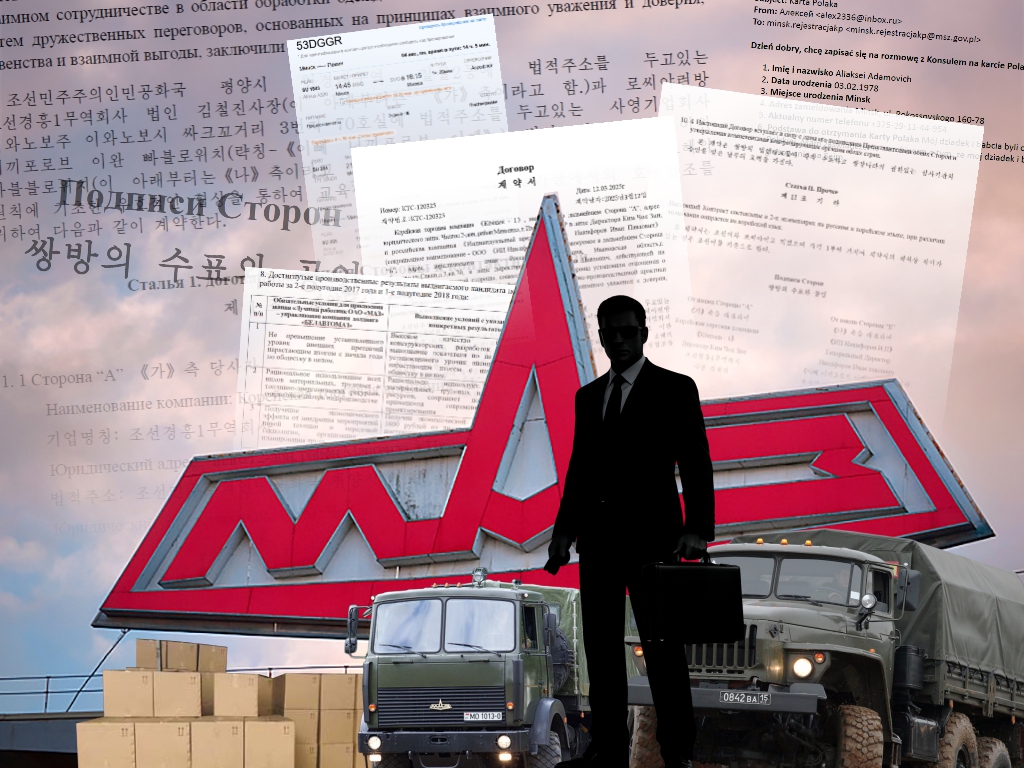

A new Dallas investigation reveals the intricate networks through which sanctioned autocracies procure military components – and the individuals who make it possible.

Sanctions and Cooperation with Russian Military-Industrial Complex

The Minsk Automobile Plant (MAZ), Belarus’s largest truck manufacturer and a cornerstone of the country’s industrial heritage, has long straddled the line between civilian commerce and military production. Established in the immediate aftermath of World War II, MAZ emerged as a critical pillar of the Soviet defense-industrial complex, producing not only heavy-duty trucks but also specialized military vehicles that formed the backbone of Soviet strategic forces.

MAZ was, and remains, recognized as the world’s largest manufacturer transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) for intercontinental ballistic missiles, supplying platforms that carried Soviet and later Russian nuclear arsenals throughout the Cold War and beyond. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, this historical military production capacity has been leveraged more overtly, with MAZ evolving into a critical node in an elaborate sanctions evasion network spanning three continents and connecting some of the world’s most heavily sanctioned regimes.

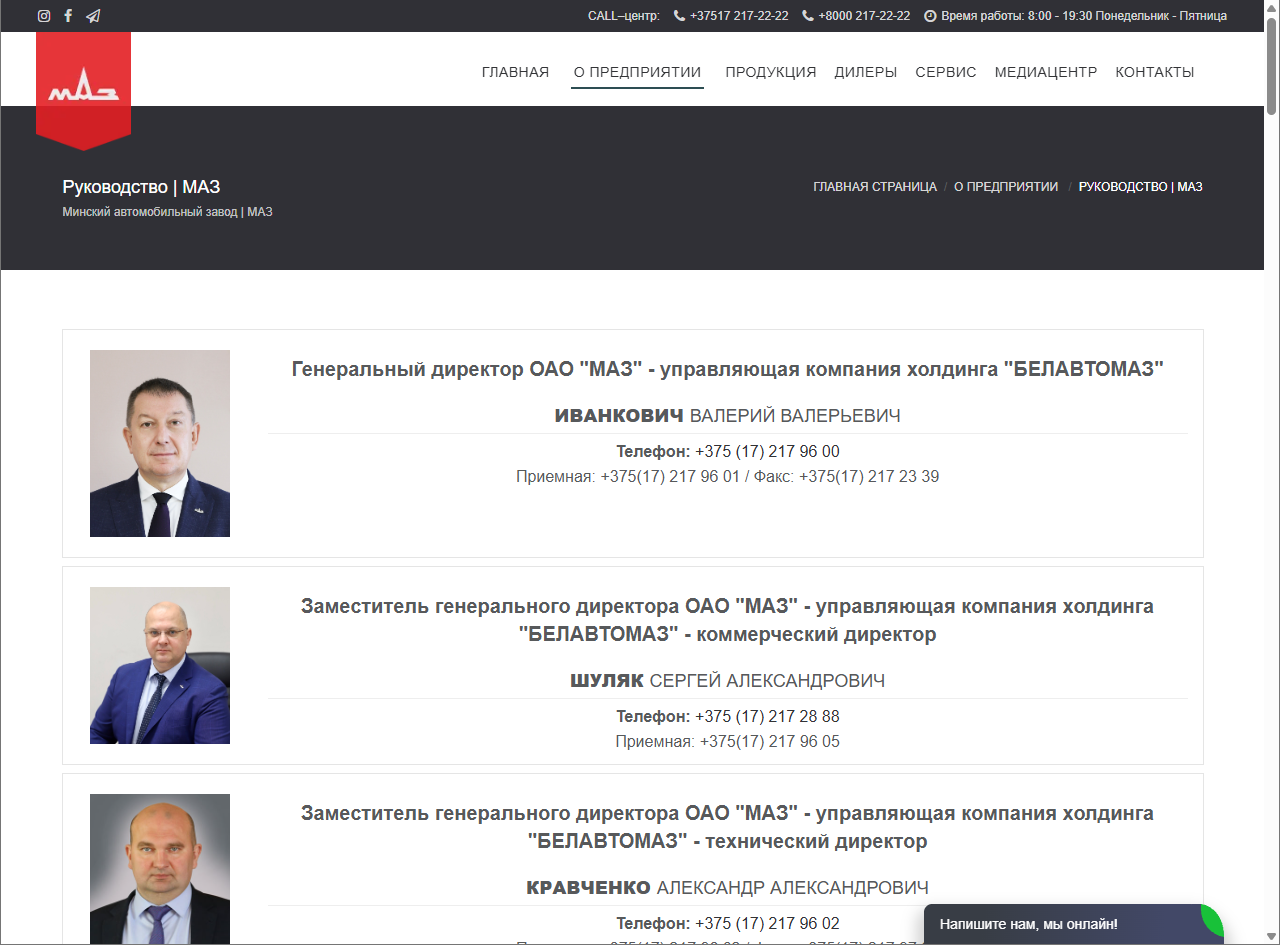

Since 2021, MAZ has been subject to Western sanctions for its role in supporting Alexander Lukashenko’s authoritarian rule and its complicity in Russia’s war of aggression. The United States Treasury Department escalated these measures in March 2023, adding MAZ to the Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list – the most severe category of economic sanctions, which effectively prohibits all transactions with American persons or entities and freezes any U.S.-accessible assets. The pressure is not limited to the enterprise itself: MAZ’s chief executive, Valery Ivankovich, along with other senior figures in the company’s leadership, has also been individually sanctioned, underscoring that Western governments view the plant’s management not as neutral industrial technocrats but as active enablers of the Belarusian regime and Russia’s war effort.

Yet rather than constraining MAZ’s operations, these sanctions appear merely to have redirected them. The company has intensified its integration into Russia’s military-industrial complex through joint production agreements, industrial localization programs, and what Moscow terms “import substitution” – bureaucratic euphemisms for the wholesale militarization of Belarus’s manufacturing capacity. Since the invasion began, Russian forces operating in Ukraine have deployed Belarusian-manufactured trucks extensively for logistics support, compensating for catastrophic losses of domestically-produced KAMAZ and Ural vehicles to Ukrainian strikes and battlefield attrition.

The scale of this integration has accelerated dramatically. As of January 2026, Russia and Belarus have expanded their collaboration from 25 initial “roadmaps” outlined in March-April 2024 to 27 active import substitution projects collectively valued at 105 billion rubles (approximately $1.1 billion), financed through preferential Russian state loans. These projects span strategic sectors including automotive manufacturing, microelectronics production, and ammunition fabrication.

Ukrainian military intelligence services assess that over 80 per cent of Belarusian industrial enterprises now fulfill Russian state defense orders, effectively completing the country’s transformation into Moscow’s primary western production base under the ideological framework of “technological sovereignty” – a term that obscures what is, in practice, colonial economic subordination dressed in the language of partnership.

The Facilitator: Aliaksei Adamovich

To understand how this system operates in practice – how sanctioned entities procure critical components, how payments circumvent financial restrictions, and how individuals navigate the shadowy intersection of legitimate commerce and international crime – one must examine the case of Aliaksei (Aleksey) Adamovich, a 47-year-old Belarusian engineer whose career trajectory reveals the operational mechanics of modern sanctions evasion.

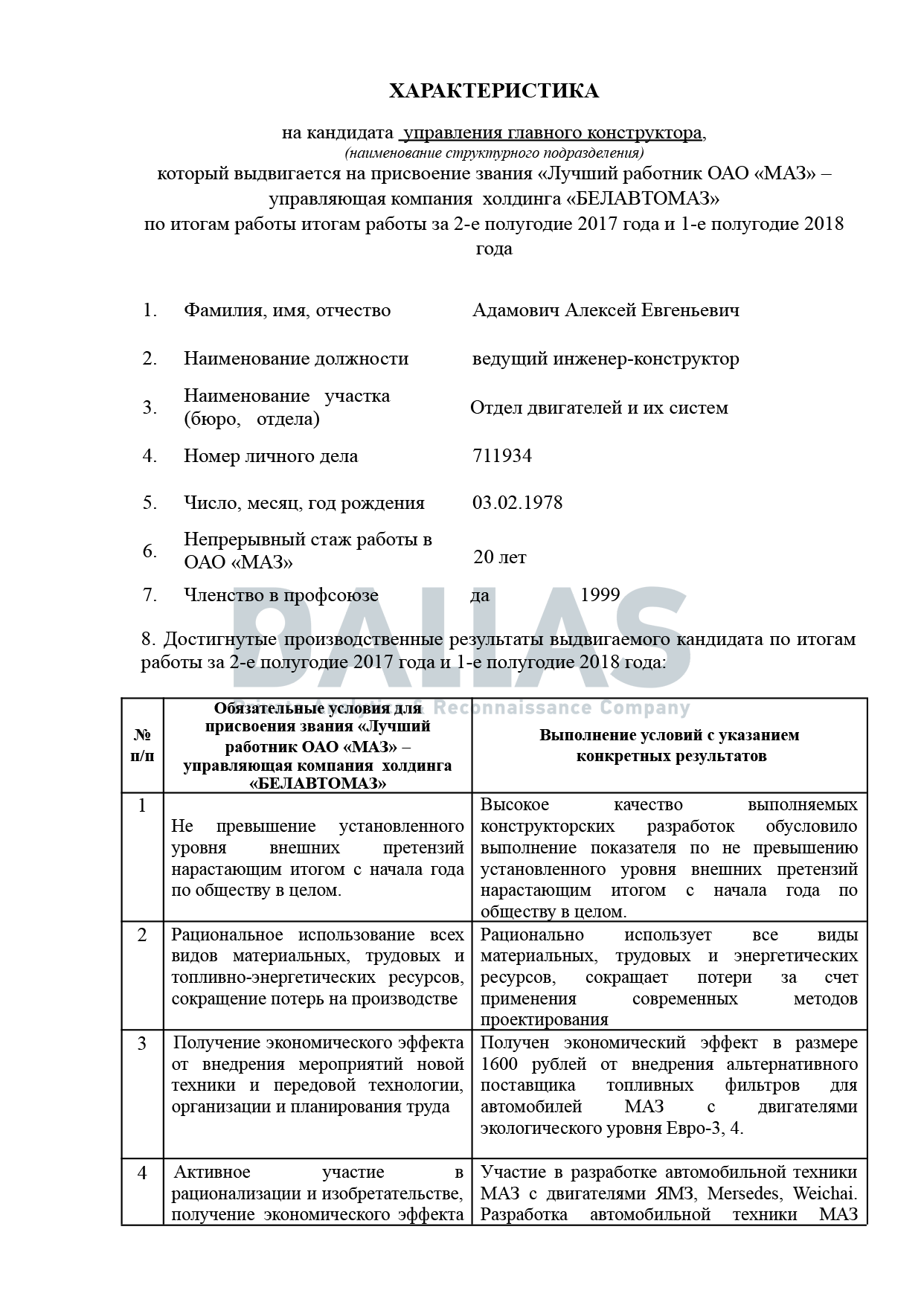

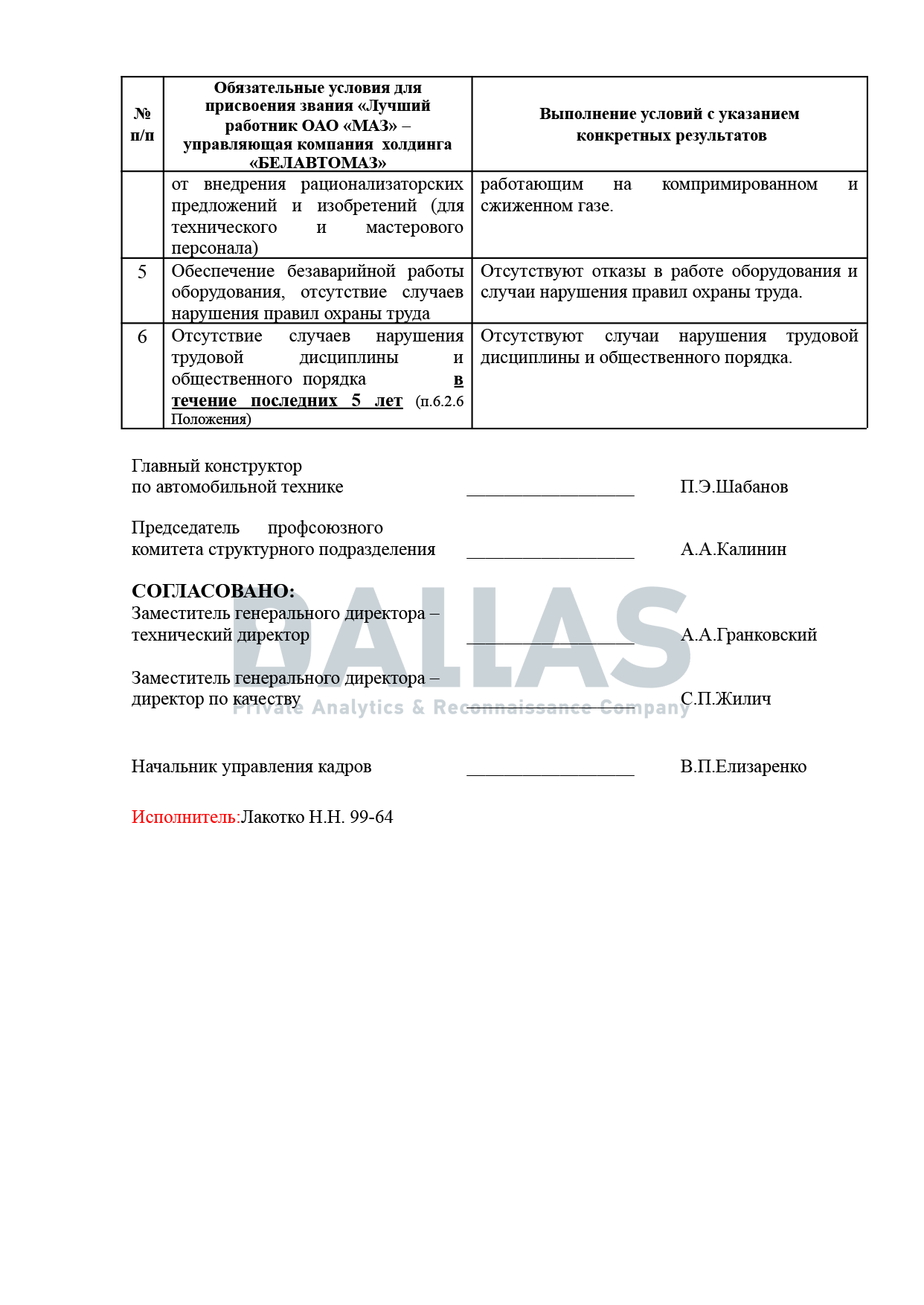

Born in 1978, Adamovich joined MAZ in 1999 as a junior engineer, steadily ascending through the company’s technical hierarchy over two decades. His personnel file reveals a competent, detail-oriented professional who accumulated comprehensive knowledge of MAZ’s production processes, engineering specifications, and – most critically – its procurement mechanisms and supplier networks. By 2018, he had risen to Lead Design Engineer in the Chief Designer’s Department, a position of considerable technical authority. That year, MAZ nominated him for a “Best Employee” award, recognizing his contributions to vehicle development programs.

Professional profile and achievements of Aliaksei Adamovych supporting nomination for the title “Best Worker of MAZ”

Website of the “Mikhanovichi Logistics Center”

This trajectory changed markedly in 2023. Adamovich formally assumed the position of Head of the Commercial Department at Open Joint-Stock Company “Mikhanovichi Logistics Center,” a state-linked entity that functions, in the assessment of sanctions compliance specialists, as a front company. Mikhanovichi ostensibly operates as a conventional logistics hub, yet in practice, it facilitates procurement for MAZ’s production lines, shielding the sanctioned manufacturer from direct exposure to its supplier networks. The arrangement allows MAZ to conduct transactions that would otherwise trigger immediate sanctions enforcement, effectively “laundering” the commercial relationships through intermediary entities.

Adamovich’s communication practices reveal the operational security measures adopted by Belarus’s sanctions-evasion apparatus. Unlike Western business professionals who maintain consistent corporate identities across communications platforms, Adamovich conducts his business correspondence through a generic free email account registered simply as “Aleksey Aleksey” [email protected] – a deliberately nondescript identity that might belong to any of tens of thousands of Russian or Belarusian citizens.

For an experienced technical manager coordinating multi-million-dollar procurement contracts involving sanctioned entities, this studied anonymity represents a calculated operational choice rather than personal eccentricity.

The Russian Connection: Arming the Ural

Ural military trucks marked with “V” and “Z” symbols used by Russian forces in the war against Ukraine

Since assuming his current role in 2023, Adamovich has functioned as the critical intermediary connecting sanctioned Russian military manufacturers with Asian component suppliers – a role that makes him indispensable to Moscow’s war effort. His most significant client is the Ural Automotive Plant (UralAZ), based in Miass in Russia’s Chelyabinsk Oblast, which has been manufacturing military trucks for the Russian armed forces since 1944.

UralAZ occupies a central position in Russia’s defense industrial base. The enterprise produces the Ural-4320 and Ural-63706 “Typhoon-U” series – heavy military trucks and Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles that form the backbone of Russian ground forces’ logistics capabilities. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, Russia has suffered catastrophic losses of these vehicles, with credible estimates suggesting that thousands of Ural-4320 trucks have been destroyed, damaged, or captured on the battlefield – a staggering rate of attrition that has placed immense pressure on UralAZ’s production lines to maintain output.

Despite billions in preferential state financing from Russia’s Industrial Development Fund, UralAZ’s manufacturing capacity remains critically dependent on foreign-sourced components, particularly from Chinese suppliers.

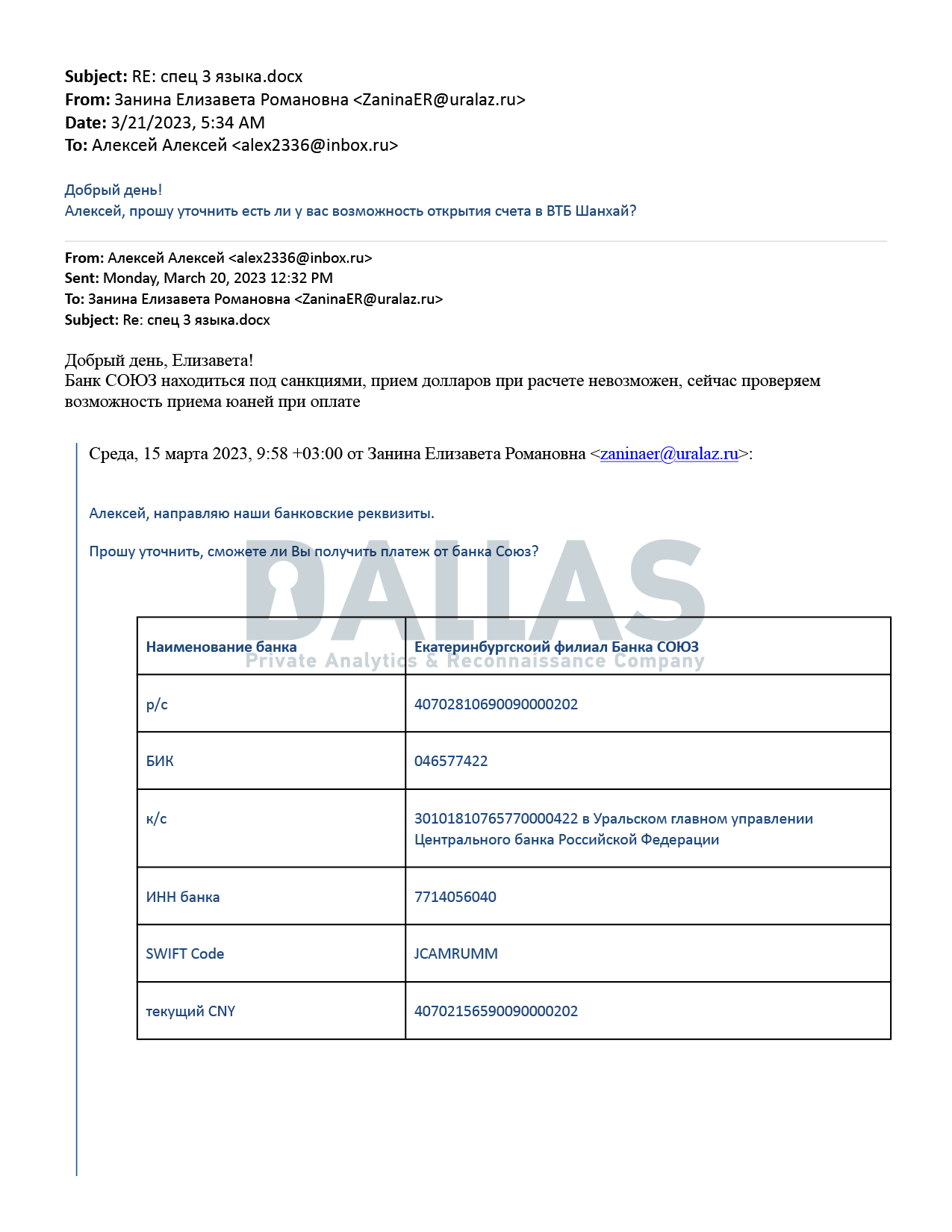

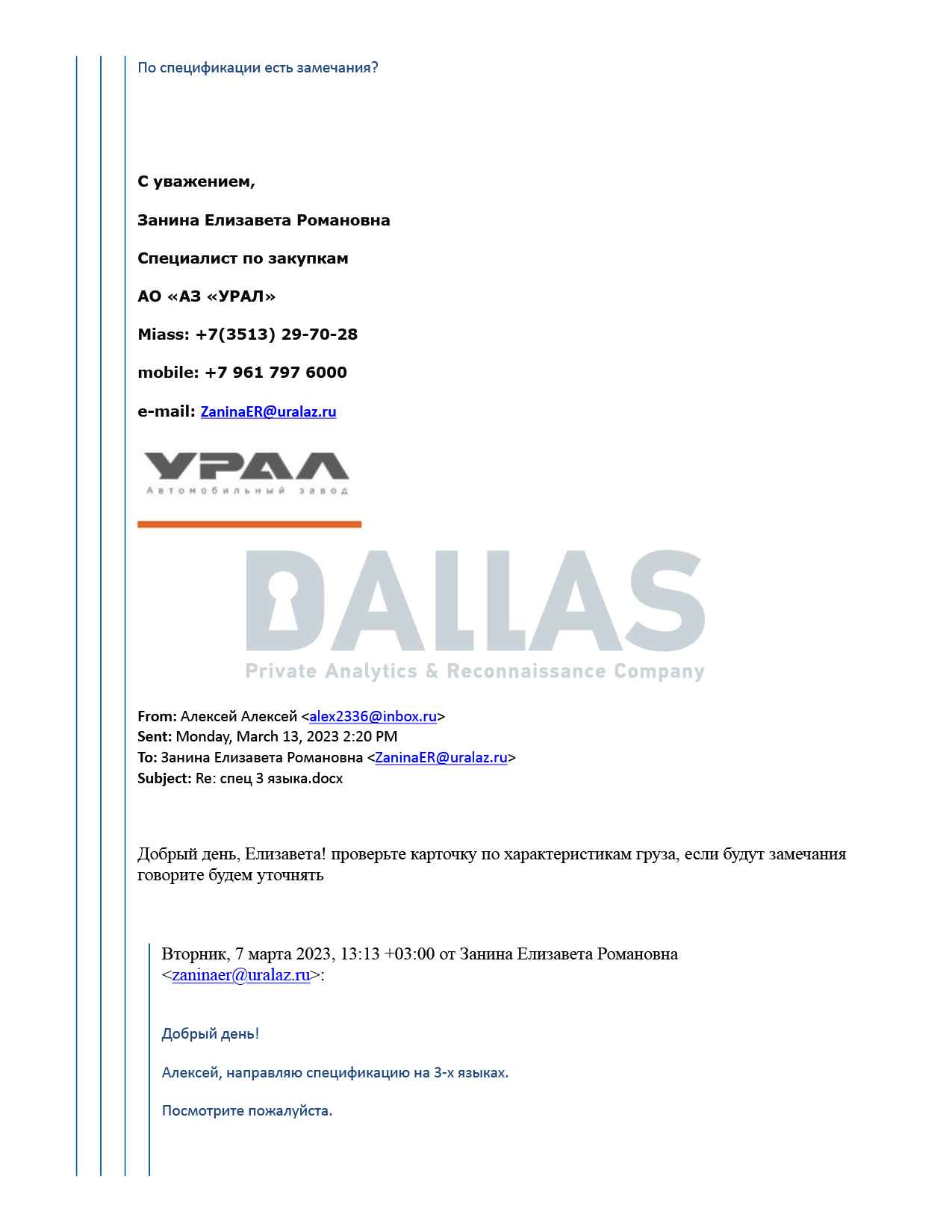

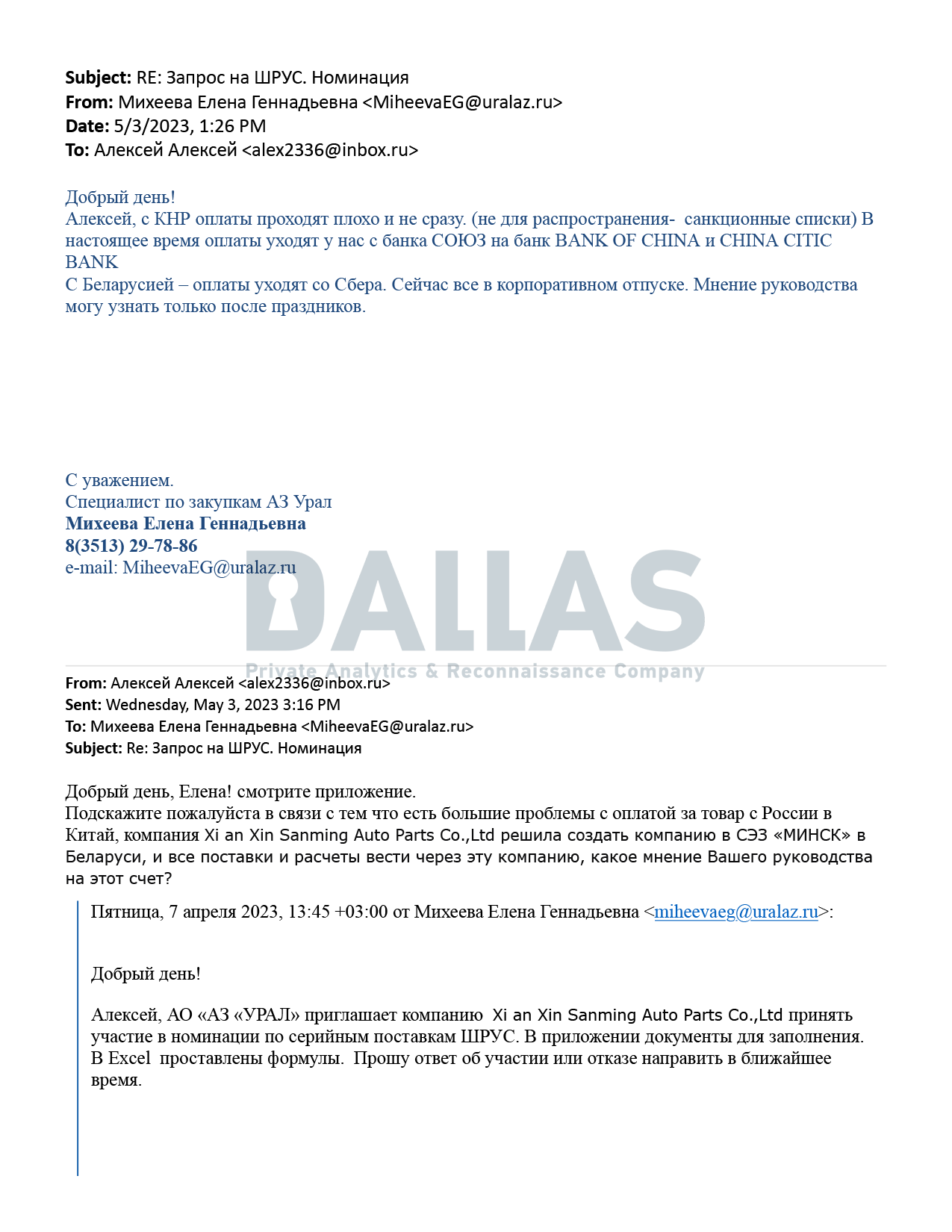

Dallas team has examined extensive email correspondence between UralAZ procurement managers – specifically Elena Mikheeva ([email protected]) and Elizaveta Zanina ([email protected]) – and Adamovich. The communications center on highly technical specifications for cardan (propeller) shafts and constant-velocity (CV) joints, critical drivetrain components for UralAZ’s heavy military chassis. These are not peripheral parts that might be easily substituted; they are load-bearing elements subject to extreme mechanical stress in off-road military operations.

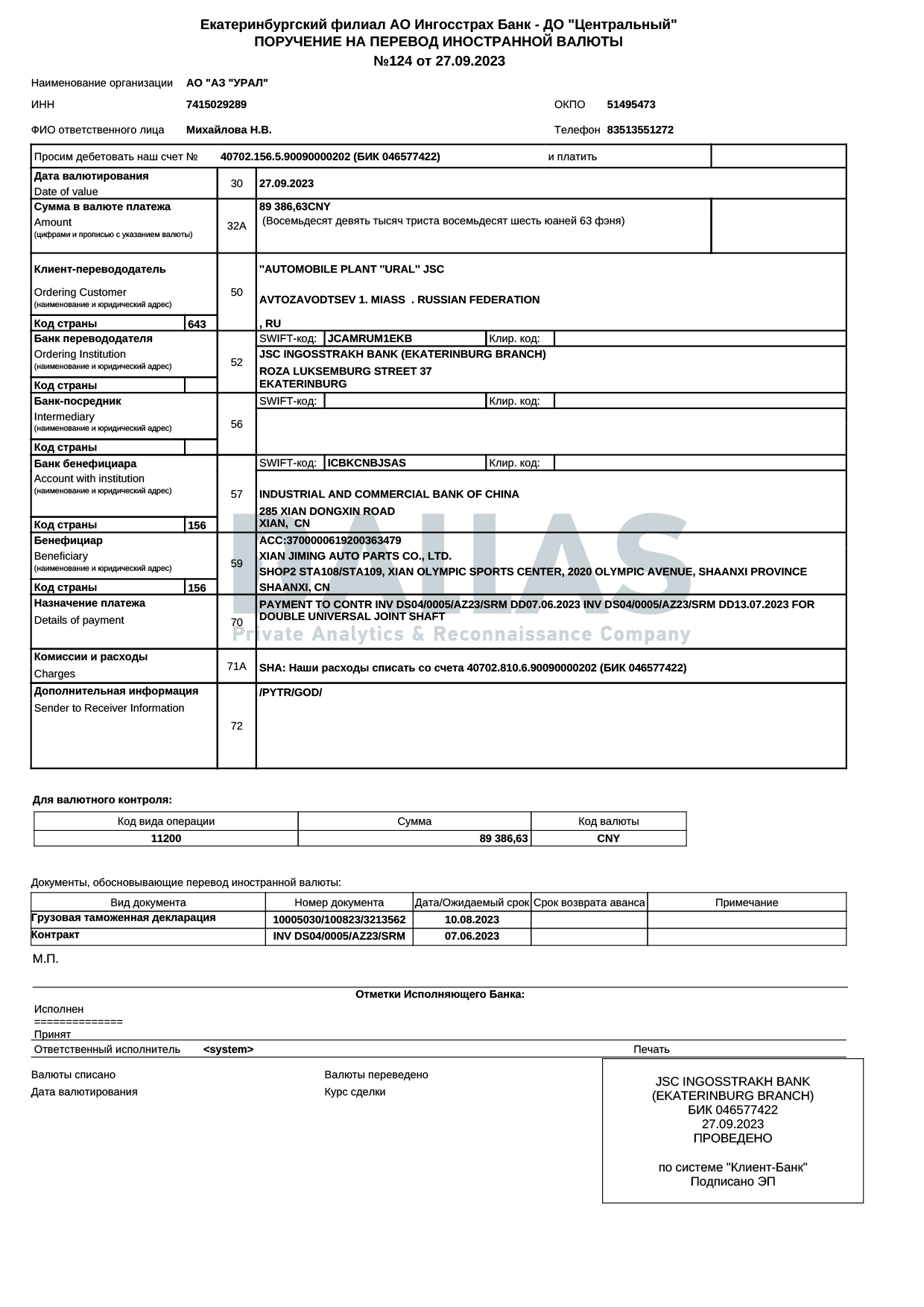

Adamovych discusses a Chinese contract payment through the sanctioned bank Soyuz with a Ural manager

One particularly revealing exchange documents the operational challenges sanctions create for these networks. In a discussion between Adamovich and Mikheeva, they attempt to structure payment for drive shafts from Chinese supplier Xi’an Xin Sanming Auto Parts Co., Ltd. The complication: UralAZ’s designated bank, Ingosstrakh Bank (formerly known as Soyuz Bank), had been sanctioned by Western authorities, rendering dollar-denominated transactions impossible. The solution they ultimately agreed upon was payment in Chinese yuan – a workaround that circumvents dollar-based financial infrastructure.

Contract order specification and authorization for foreign currency transfer between UralAZ and Xi’an Xin Sanming Auto Parts

The Xi’an Connection: Military Components in Commercial Disguise

The case of Xi’an Xin Sanming Auto Parts Co., Ltd. exemplifies the complex role Chinese manufacturers play in sustaining Russia’s military production. Based in Xi’an, capital of Shaanxi Province in northwestern China, this company officially produces automotive drivetrain components for civilian commercial vehicles. Its product catalog includes cardan shafts, CV joints, and related steering and suspension components – standard items in global automotive supply chains.

Yet internal marketing materials analyzed by Dallas disclose a different operational focus. In a presentation specifically targeted at the Russian market, Xi’an Xin Sanming openly advertises that its products are suitable for military vehicle applications.

Further correspondence reveals even more elaborate evasion schemes. In one exchange, UralAZ manager Elena Mikheeva and Adamovich discuss a proposal from Xi’an Xin Sanming to establish a subsidiary company within the Special Economic Zone “Minsk” in Belarus. This arrangement would allow all deliveries and financial settlements to flow through Belarusian rather than Chinese or Russian jurisdiction – adding another layer of legal complexity for sanctions enforcement authorities while providing Xi’an Xin Sanming with plausible deniability regarding the ultimate end-use of its products.

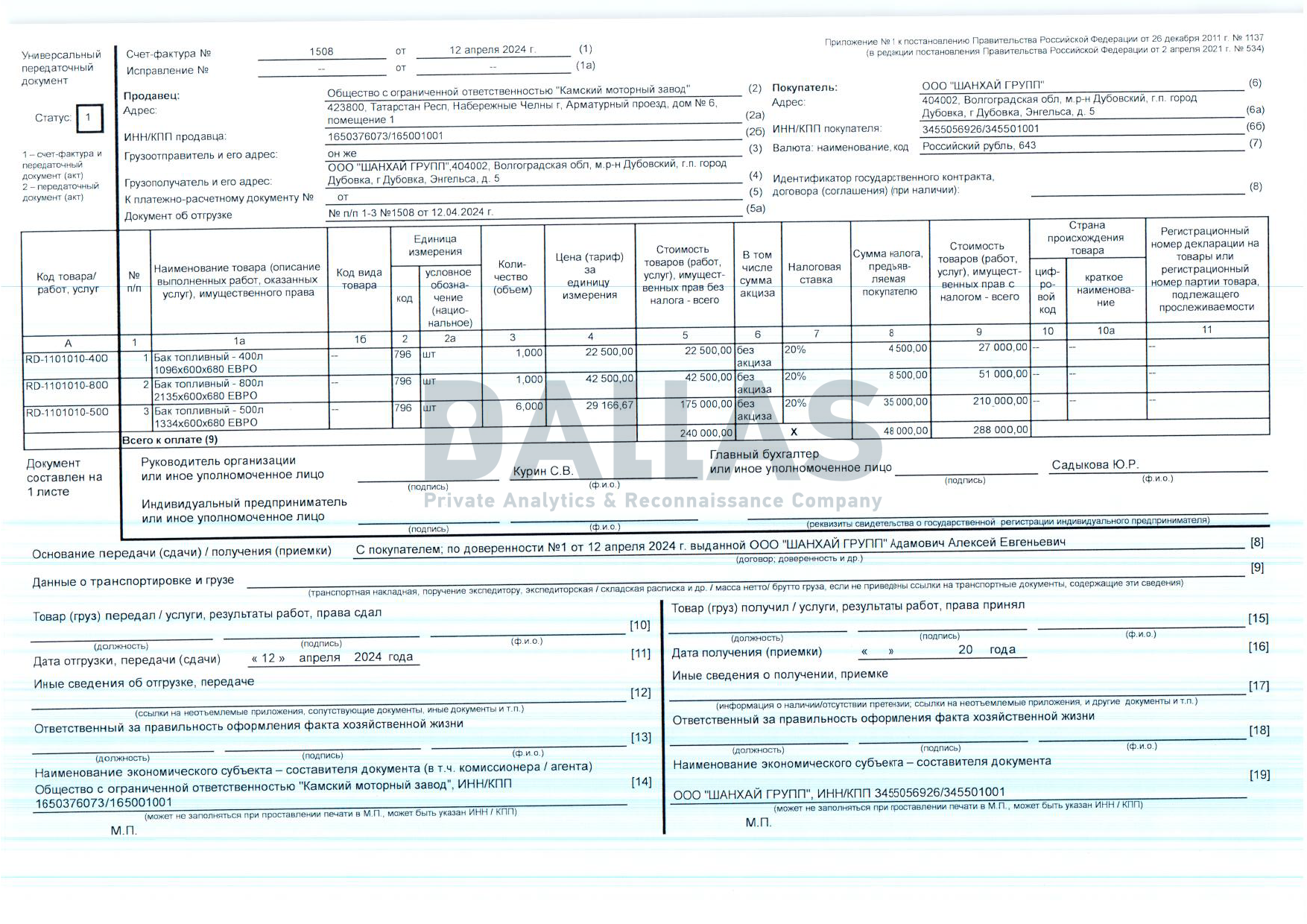

Another transaction documented in Adamovich’s correspondence demonstrates the proliferation of shell companies that facilitate these networks. Acting as a representative of “Shanghai GROUP LLC” – an entity established only in 2023 in Russia’s Volgograd Oblast with minimal authorized capital of 10,000 rubles (approximately $100) – Adamovich negotiated the purchase of fuel tanks for trucks from the Kama Motor Plant in Tatarstan.

Since February 2022, Russia has dramatically expanded its ecosystem of such intermediaries, creating thousands of ephemeral corporate entities faster than Western sanctions regimes can identify and designate them.

These examples underscore Adamovich’s unique value proposition: his engineering background allows him to serve not merely as a purchasing agent but as a technical intermediary who can evaluate component specifications, verify quality standards, and mediate between Russian military manufacturers’ requirements and Asian suppliers’ capabilities. This technical fluency, combined with his institutional knowledge of MAZ’s procurement systems and his trusted status within Belarus’s security apparatus, makes him an indispensable figure in sanctions circumvention.

The Trusted Lieutenant: KGB Approval and Global Mobility

In Belarus’s authoritarian system, foreign economic activity involving sanctioned entities like MAZ is not conducted without state oversight. The State Security Committee – still known by its Soviet-era acronym KGB – exercises comprehensive control over such activities through a permit-based system governing foreign travel, technology transfers, and commercial engagement with dual-use goods.

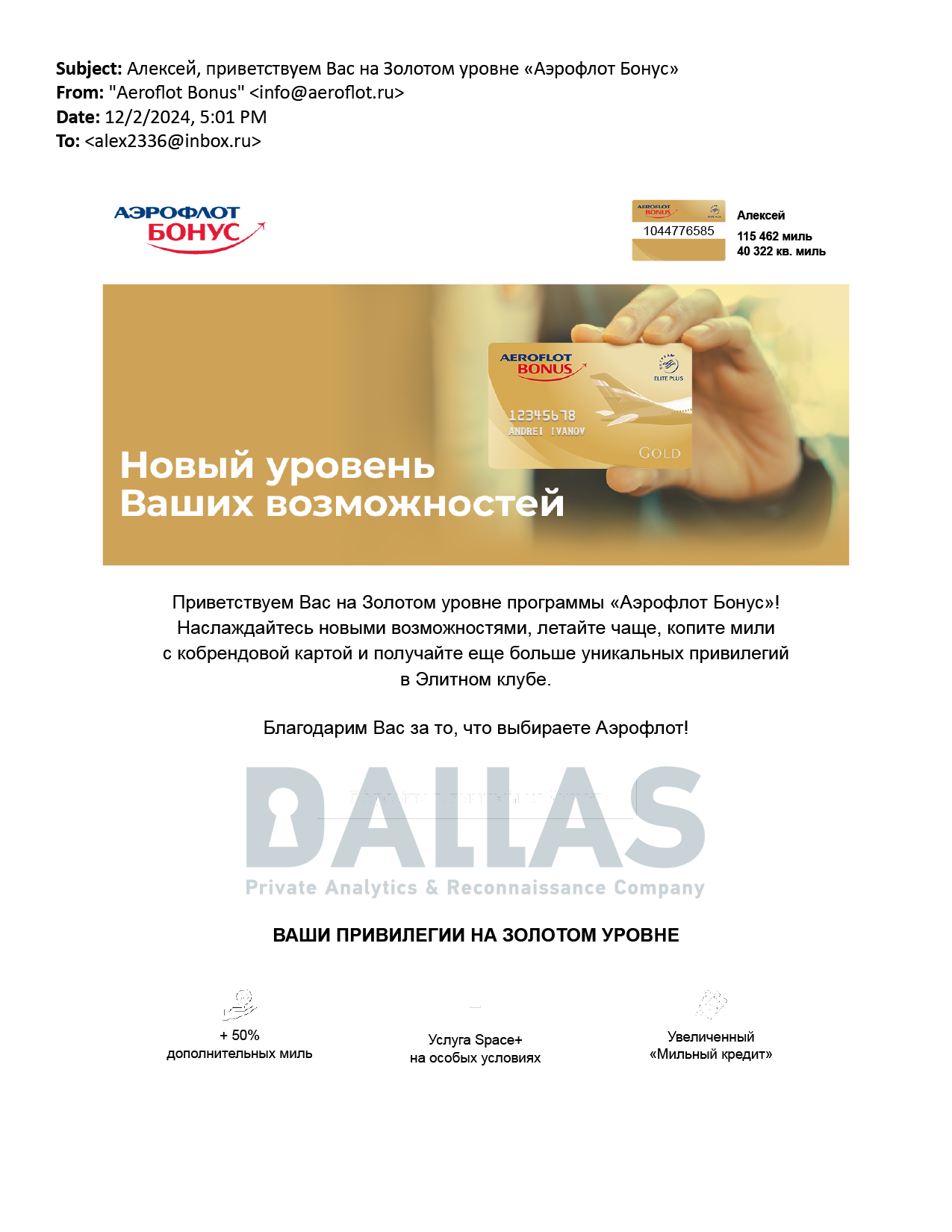

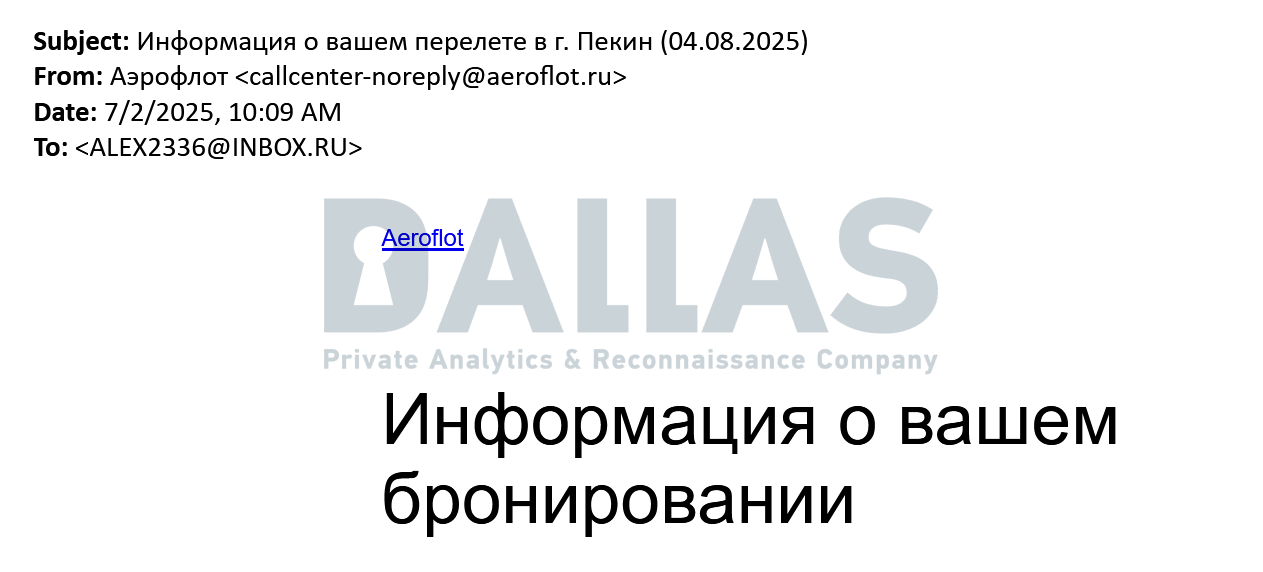

Adamovich’s freedom of operation suggests he occupies a privileged position within this system as a trusted lieutenant of the Lukashenko regime. According to records from Russian flag carrier Aeroflot, he achieved Gold-tier frequent flyer status in 2024 – a designation requiring extensive international travel.

His documented destinations in August 2025 alone included multiple Chinese cities: Beijing, Wenzhou, Xi’an, and the resort destination of Sanya (the latter accompanied by his wife and two children, suggesting a combined business-leisure trip that indicates both financial means and official approval for family travel).

For context, the average Belarusian faces significant restrictions on international movement. Western sanctions and the country’s pariah status have severely constrained access to European and American travel. Many Belarusians who oppose the Lukashenko regime have been denied passports or placed on travel ban lists.

The European Escape Route: Poland’s Karta Polaka

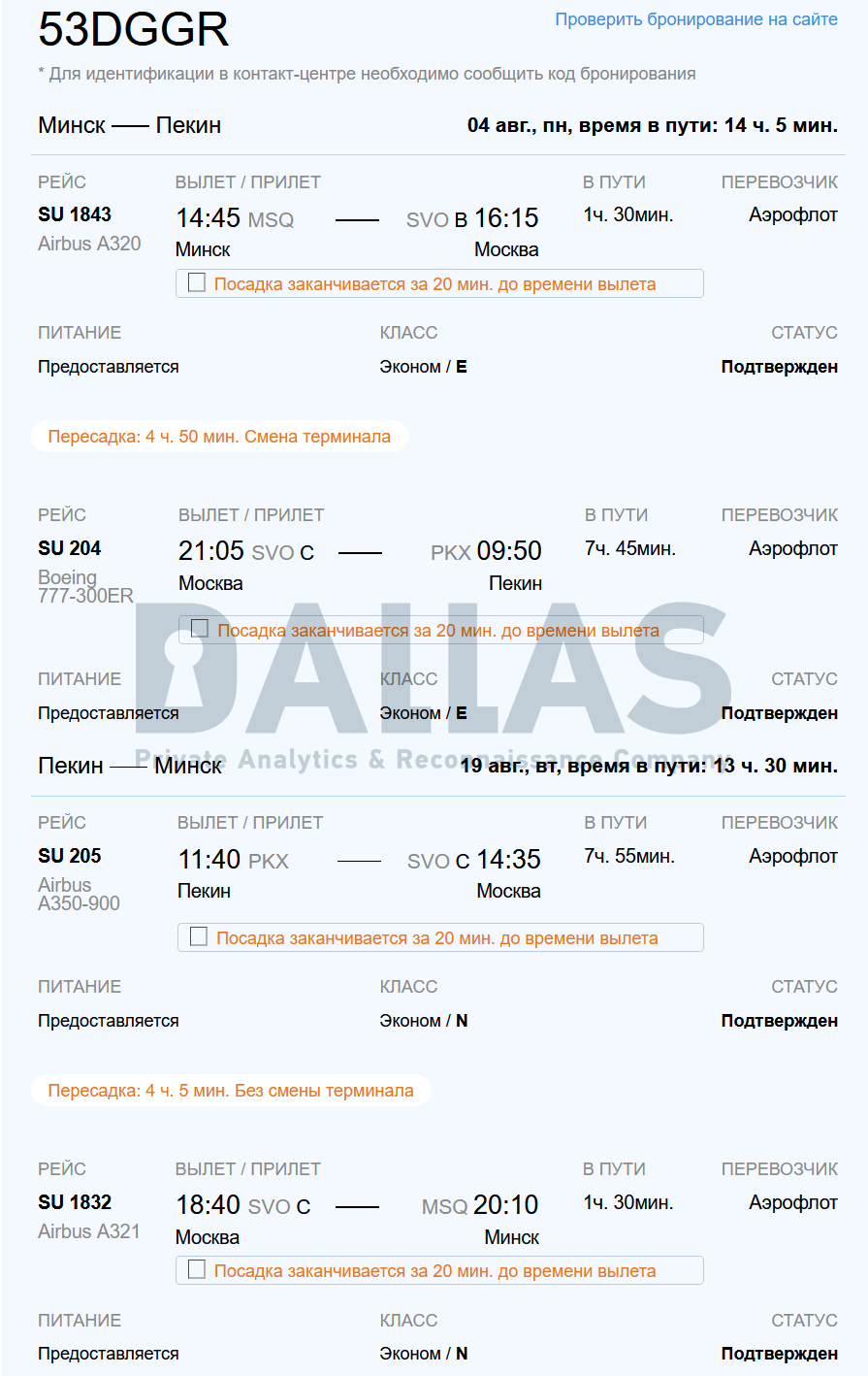

Yet for all his apparent loyalty to the Lukashenko regime and his intimate involvement in Russia’s military supply chains, Adamovich has simultaneously pursued an exit strategy that reveals either remarkable cynicism or pragmatic insurance planning: he is seeking Polish citizenship.

Internal records reviewed by Dallas confirm that Adamovich registered for a formal interview at the Polish Consulate in Minsk to obtain a Karta Polaka (Pole’s Card) – a document issued by the Polish government to individuals who can demonstrate Polish ethnic heritage. The Karta Polaka is far more than symbolic recognition; it provides a legal pathway to Polish permanent residency and, subsequently, full citizenship through an expedited “fast-track” process that typically takes only one year.

In his application to the Polish Consul, Adamovich stated that his paternal grandfather and grandmother were citizens of the Republic of Poland and provided archival evidence showing they appeared on voting registers for the Sejm (Polish Parliament).

This case illustrates a troubling gap in sanctions enforcement: the focus on corporate entities and high-profile oligarchs while operational-level facilitators who enable sanctions evasion move freely through Western jurisdictions. Dallas will notify Polish security services regarding Adamovich’s application and provide detailed documentation of his activities.

The Pyongyang Connection: Belarus Meets North Korea

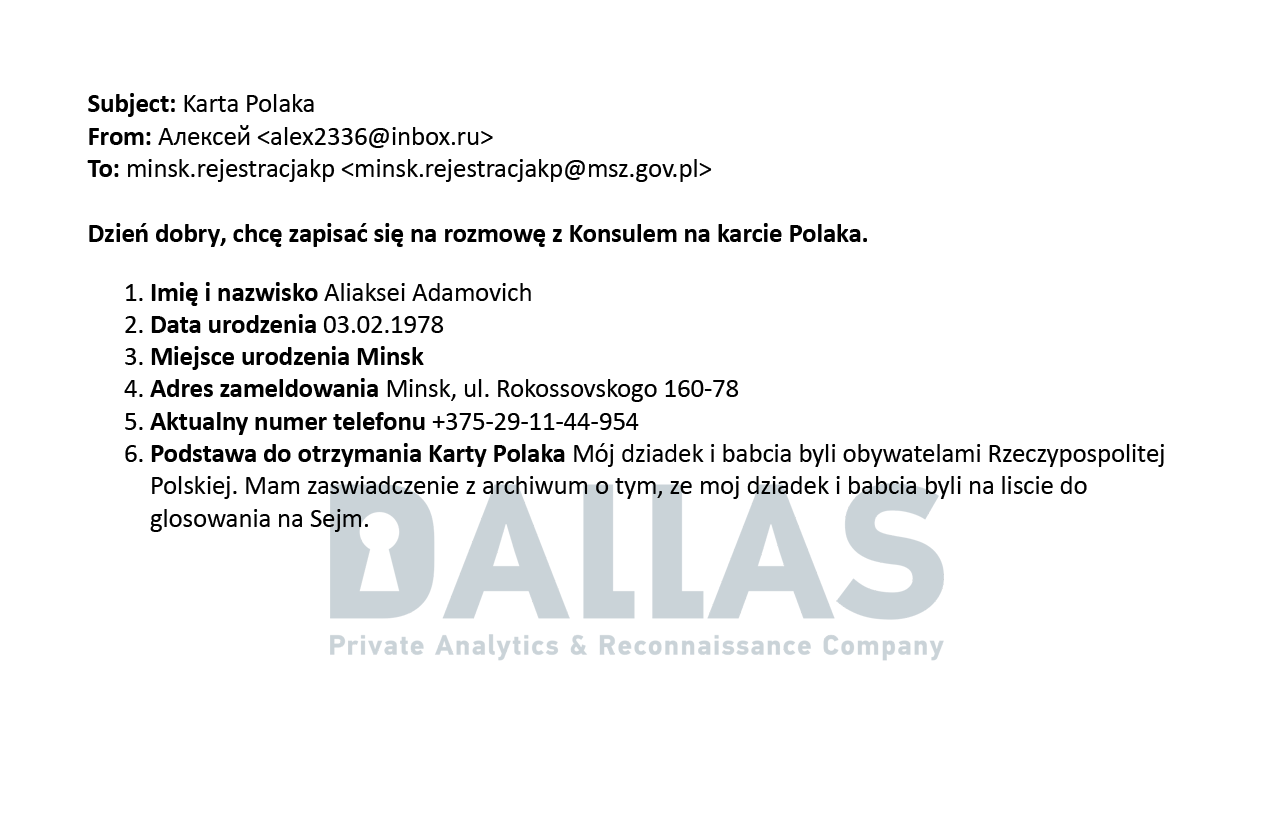

Yet the most serious revelation in Adamovich’s activities involves a jurisdictional escalation that transforms his conduct from sanctions evasion into something approaching international criminal conspiracy: his facilitation of automotive component procurement from North Korea on behalf of MAZ.

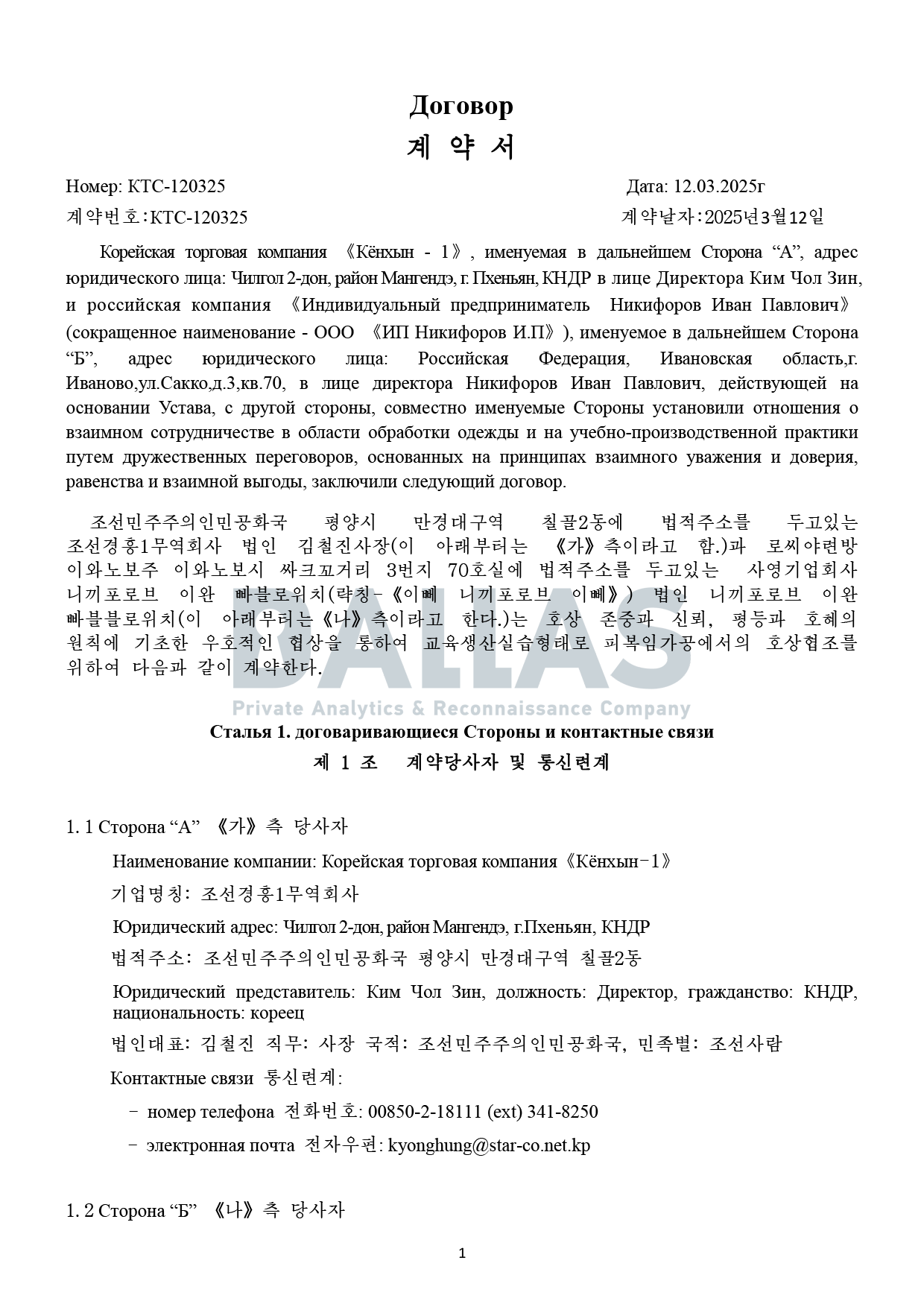

A paper trail of records reviewed by Dallas confirms that MAZ, Belarus’s state-owned truck manufacturer, ordered substantial shipments of critical automotive components from Chosun Kyonghun 1 Trading Company, a Pyongyang-based entity operating under North Korean state control.

The 2025 procurement list is comprehensive and technically specific: precision steering systems, complex electronic control modules, polyurethane hoses engineered for Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) emission control systems, wiring harnesses, and suspension components. These are not marginal purchases or isolated transactions; they represent systematic procurement arrangements that require ongoing technical coordination, quality control procedures, and sustained commercial relationships.

Under international law, such arrangements constitute unambiguous violations of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 2397 (December 2017) and 2375 (September 2017), which comprehensively prohibit all trade with North Korean state entities and mandate the cessation of all new commercial relationships with DPRK economic actors. These resolutions do not create ambiguous gray zones or regulatory complexity requiring legal interpretation. They are categorical prohibitions: no trade, no exceptions, no technical loopholes. More critically, transactions with North Korean entities are characterized in sanctions law as per se violations – the mere fact of the transaction is sufficient for prosecution.

For Adamovich personally, conviction under the U.S. International Emergency Economic Powers Act carries potential sentences up to 20 years imprisonment and fines exceeding $1 million.

The Shenyang Sanitization: Chinese Intermediaries and North Korean Control

Yet once again, the architects of this scheme have not conducted the illicit trade directly. According to documents reviewed by Dallas, MAZ simultaneously executed formal procurement contracts with Shenyang Raimond Industrial Co., Ltd., a company registered in the Shenyang Pilot Free Trade Zone in Liaoning Province, northeastern China.

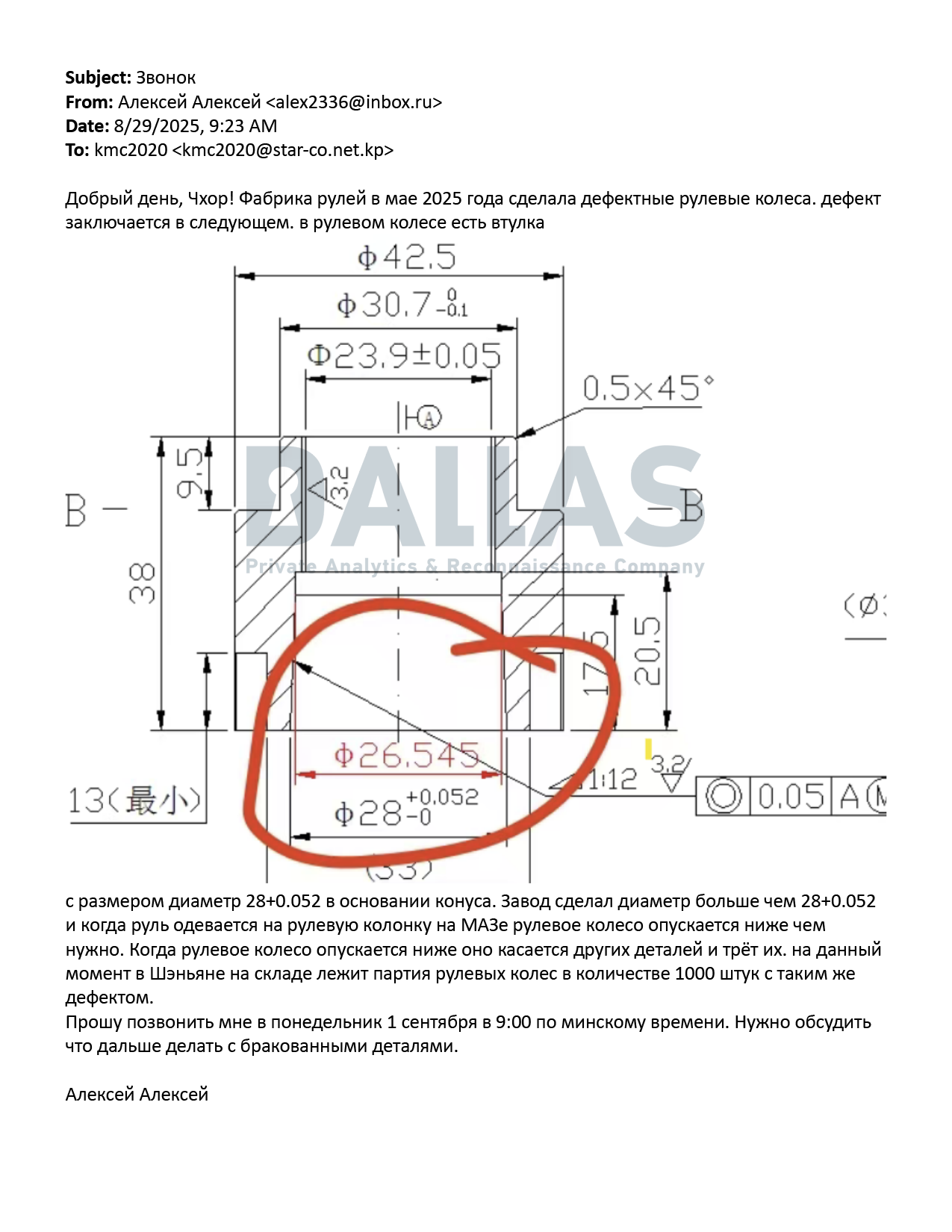

The operational reality, however, is starkly different. Despite the Chinese legal documentation and corporate registration, Adamovich personally conducts all substantive business functions directly with Tsoy Chhor (조종호), a North Korean national serving as the de facto operational director of the arrangement. According to correspondence obtained by Dallas, Tsoy personally oversees all critical technical approvals and engineering specifications for components; personally certifies all quality control inspections and manufacturing compliance testing; and personally coordinates all financial settlements and payment transfers.

In this architecture, Shenyang Raimond Industrial functions not as a genuine manufacturer or even a legitimate trading intermediary, but rather as what sanctions compliance specialists term a “shell entity” or “front company” – a legal fiction designed exclusively to provide geographic and corporate distance between the actual North Korean supplier and the Belarusian purchaser.

This operational structure bears striking resemblance to documented North Korean sanctions evasion networks that have been identified and designated by Western authorities. Shenyang, and Liaoning Province more broadly, has emerged over the past decade as the primary geographic nexus through which North Korean front companies conduct illicit procurement operations targeting third countries. According to assessments by the National Committee on North Korea, over 90 per cent of North Korea’s international trade flows through China, predominantly via intermediaries concentrated in Liaoning Province, which shares a 1,420-kilometer border with the DPRK.

The Ivanovo Contract: North Korean Labour Under Commercial Cover

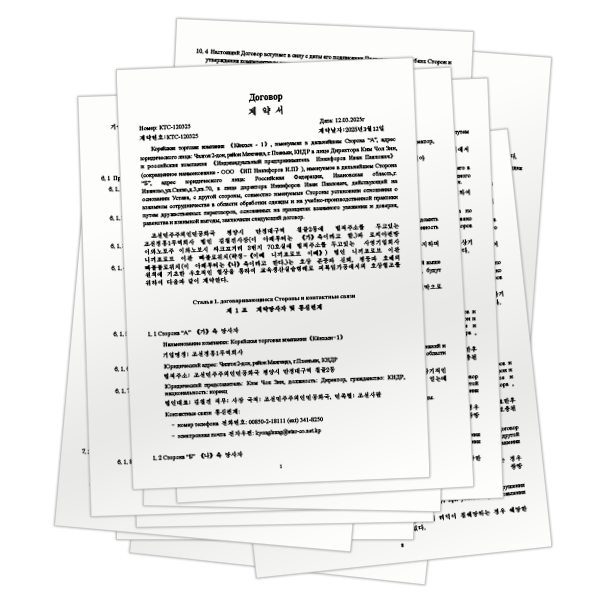

Adamovych and Chhor exchange a contract related to the training of North Korean workers in “sewing production” in Russia

One additional element in the correspondence between Adamovich and Tsoy Chhor warrants particular scrutiny: a contract between the Kyonghun 1 company (based in Chilgol, a Pyongyang suburb known to house multiple sanctioned North Korean trading corporations) and Ivan Pavlovich Nikiforov, described simply as an “individual entrepreneur from Russia.” The five-year agreement stipulates what is characterized as a “study trip” for 460 North Korean students allegedly studying garment manufacturing, who would be dispatched to the city of Ivanovo in Russia’s textile industrial region.

The contract’s stipulated compensation structure creates the strong impression that “garment manufacturing training” serves as cover for something altogether different – likely military-related. The agreement specifies monthly payments of $500 for “students,” $600 for “employees,” and $700 for a “director” – figures that bear no resemblance to legitimate vocational education programs and raise immediate questions about the true nature of the work.

For context, typical reported official wages for North Korean state-assigned factory work hover around $1-3 USD per month based on black-market exchange rates, with the vast majority of even this pittance confiscated by state authorities.

Download the full contract

계약서 договор ИП.pdf

This component of Adamovich’s activities connects Belarus not merely to sanctions evasion but to potential participation in forced labor arrangements that constitute serious human rights violations. If substantiated, such involvement could expose Adamovich and MAZ to prosecution under human trafficking statutes in addition to sanctions violations.

The Correspondence: A Paper Trail of Evasion

The banality of the correspondence underscores a troubling reality about sanctions evasion networks: they function through the accumulated efforts of competent professionals performing technical tasks that are, in themselves, unremarkable. Adamovich does not style himself as an arms trafficker or sanctions-busting operative; he operates as a procurement specialist solving logistics problems. Yet the systemic effect of his work – when those components enable the production of vehicles that Russian forces deploy to obliterate Ukrainian cities and murder Ukrainian children – transforms technical competence into complicity in war crimes.

The Adamovich case also exposes critical weaknesses in Western sanctions architecture. Despite being subject to SDN designation since 2023, MAZ continues to procure critical components, process payments, and maintain international commercial relationships. Despite his documented role facilitating military procurement for sanctioned entities, Adamovich travels freely through Europe, conducts business deals, and is pursuing EU citizenship through Poland. Despite clear prohibitions on North Korean trade, components from Pyongyang-based entities flow through Chinese intermediaries to Belarusian manufacturers with apparent impunity.